Always under construction!

CV

(Last updated 09/2024).

Here are some things I’ve worked on:

Primordial non-Gaussianity:

“Inflation” is our model for the Universe in its earliest moments. There is a zoo of possible inflationary models, which we can only sort through based on their downstream impact on cosmological measurements. For the forseeable future, the best way to characterize an especially interesting subset of these models (multi-field models) is with galaxy surveys. This is because galaxy surveys are especially well-suited for measuring local primordial non-Gaussianity (LPNG), which is an observable signature in the statistics of galaxies that is closely associated with multi-field inflation.

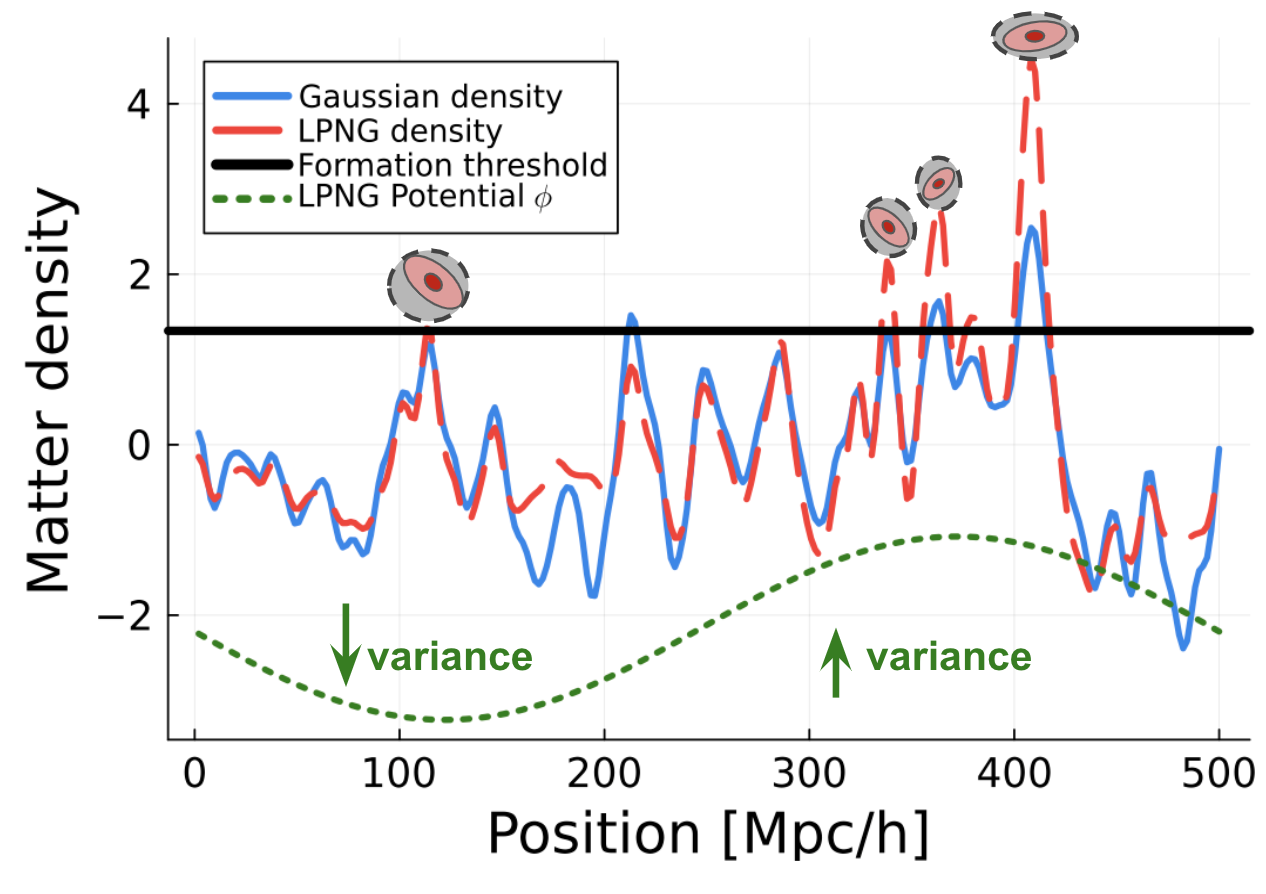

Specifically, I work on using the influence of early universe physics on galaxy formation through the phenomenon of galaxy bias, which connects the statistics of primordal flucturations to the statistics of galaxies. For LPNG, this kind of galaxy bias can be understood as due to the gravitational potential [1] modulating the number of galaxies that form in different parts of the universe through the variance of the matter density field:

This galaxy bias effect will be the primary driver of constraints on multi-field inflation for the forseeable future, and I’m excited to continue working on it!

Understanding Large-scale Structure

- The information content of tracers: The night of large-scale structure is dark, but it offers lampposts in the form of luminous tracers, like galaxies and hot gas. It is not very easy to describe how these tracers are located in space, especially when they are almost close enough to overlap. I spent a little time working on this directly, but am thinking about it all the time!

- Massive neutrinos: More than ten million neutrinos from the early universe are passing through your body right now. Neutrinos are sub-atomic particles predicted by the Standard Model, but what was not predicted is that they have mass. It turns out they do have mass, and cosmological measurements can place the tightest upper bound on that mass - that is - if we understand how neutrinos affect large-scale structure. I worked toward this goal by improving the treatment of massive neutrinos in cosmological simulations.

Modern Numerical Tools for Cosmological Inference

- Differentiable forward models, optimization, and sampling: Suppose you have to climb a hill as fast as possible. Going straight up seems a pretty good option, but what direction is “up”? Gradient-based optimization and sampling methods use this directional information to move around spaces of very large dimension. When this information is avaliable, it makes the process of finding the best parameters for a given physical model and their uncertainties much easier. To do this, however, the model has to be differentiable - and I’ve worked on developing this capability for one model or another since I started at Berkeley!

- Active Learning: Budgeting is an (un)fortunate part of daily life, but also an important part of scientific investigation. To actually learn something from a data analysis, we want to estimate parameters of a model and attach an uncertainty to them. When the model for the physical process in question is expensive (e.g. a simulation that takes hundreds of years on your laptop), we can’t afford to run it enough times to capture this uncertainty in the usual way. Instead, we can think very carefully about what parameter values we want to evaluate our model at using active learning. I used some machine learning tools (normalizing flows, gaussian processes, and neural networks) to test a new strategy to do this.

I’ve had the pleasure of working with several people on these problems, including: Uroš Seljak, Zack Li, the CPAC group at Argonne National Lab, Sukhdeep Singh, and others at BCCP & LBNL. I’m also a member of the DES, LSST-DESC, and CMB-S4 collaborations.

Notes:

-

For the aficionados, the potential \(\phi\) here is the gauge-invariant Bardeen potential, which, in the late universe, is the negative version of the familiar Newtonian potential \(\Phi\). ↩